The Limits of Single Frame Delivery

Okay, so what about Fast Sync? Unlike G-SYNC, it works with any display, and while it’s still a fixed refresh rate syncing solution, its third buffer allows the framerate to exceed the refresh rate, and it utilizes the excess frames to deliver them to the display as fast as possible. This avoids double buffer behavior both above and below the refresh rate, and eliminates the majority of V-SYNC input latency.

Sounds ideal, but how does it compare to G-SYNC?

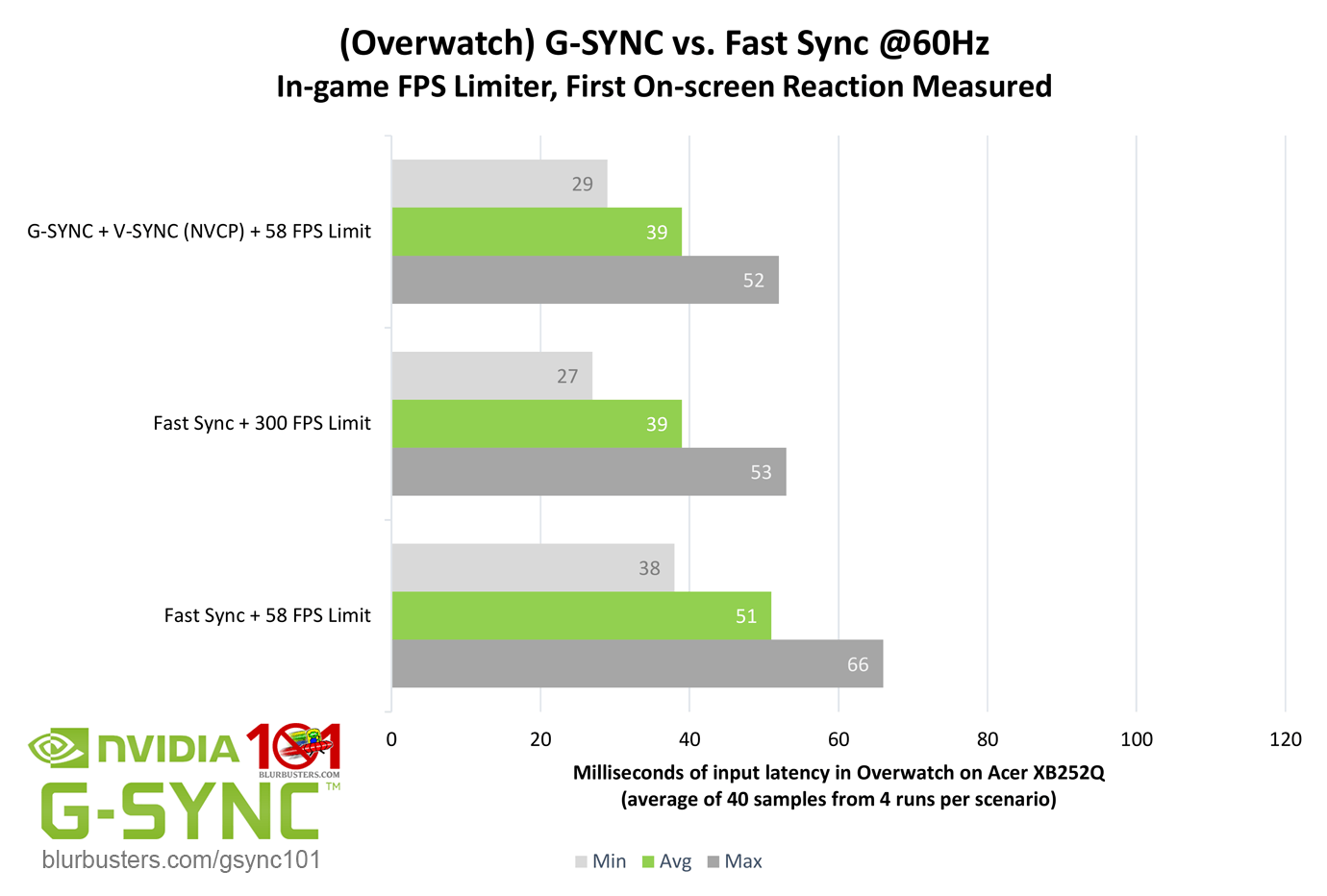

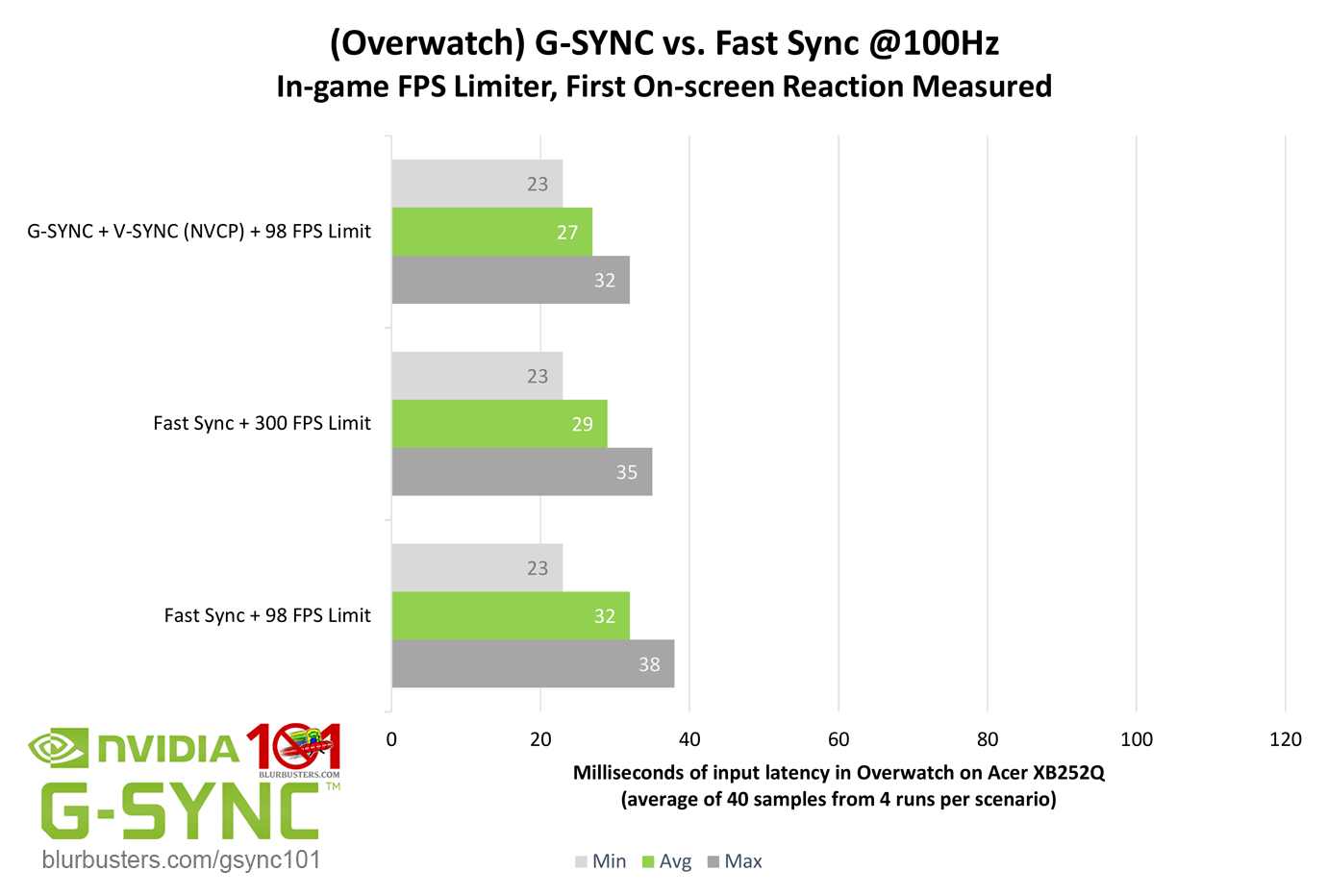

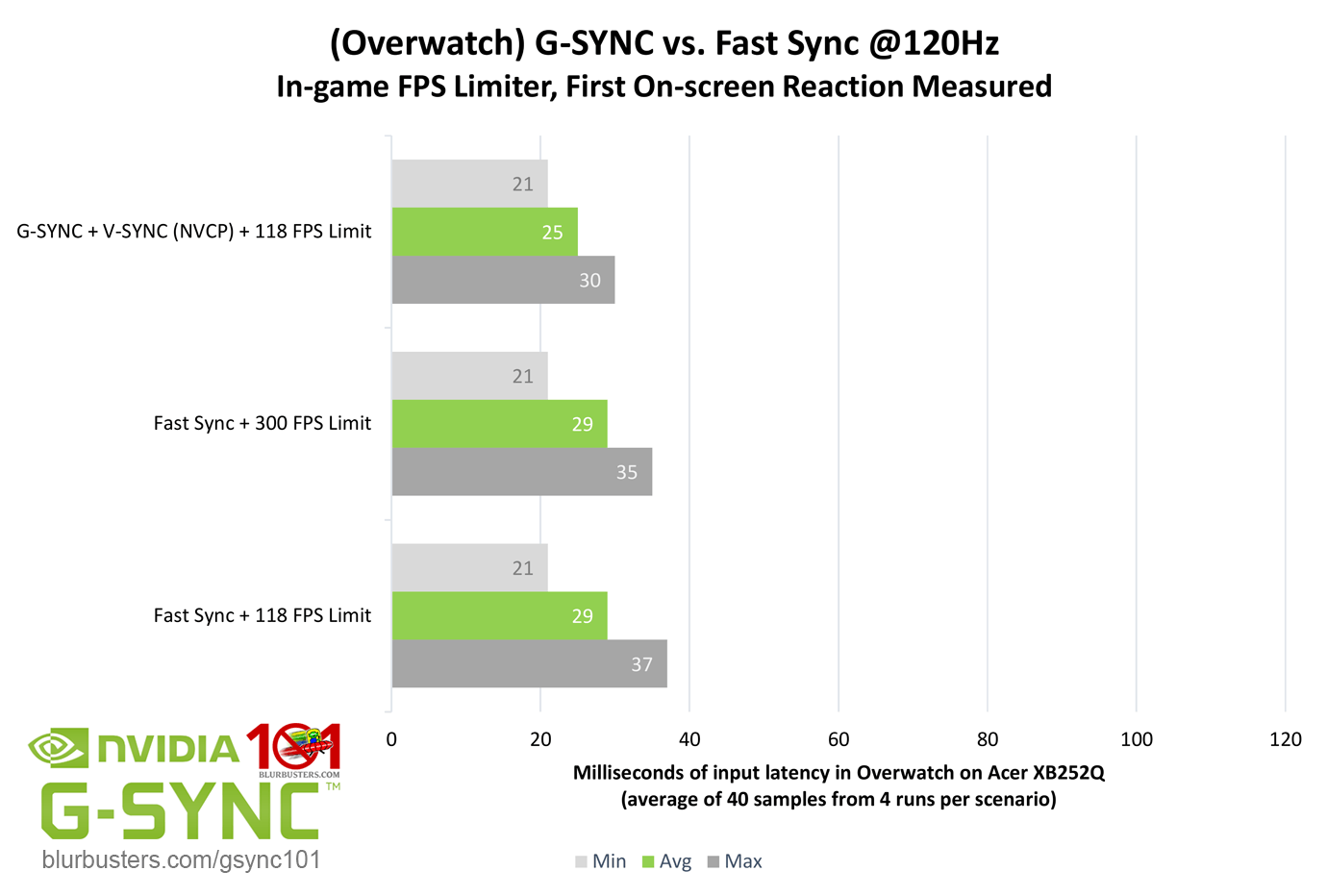

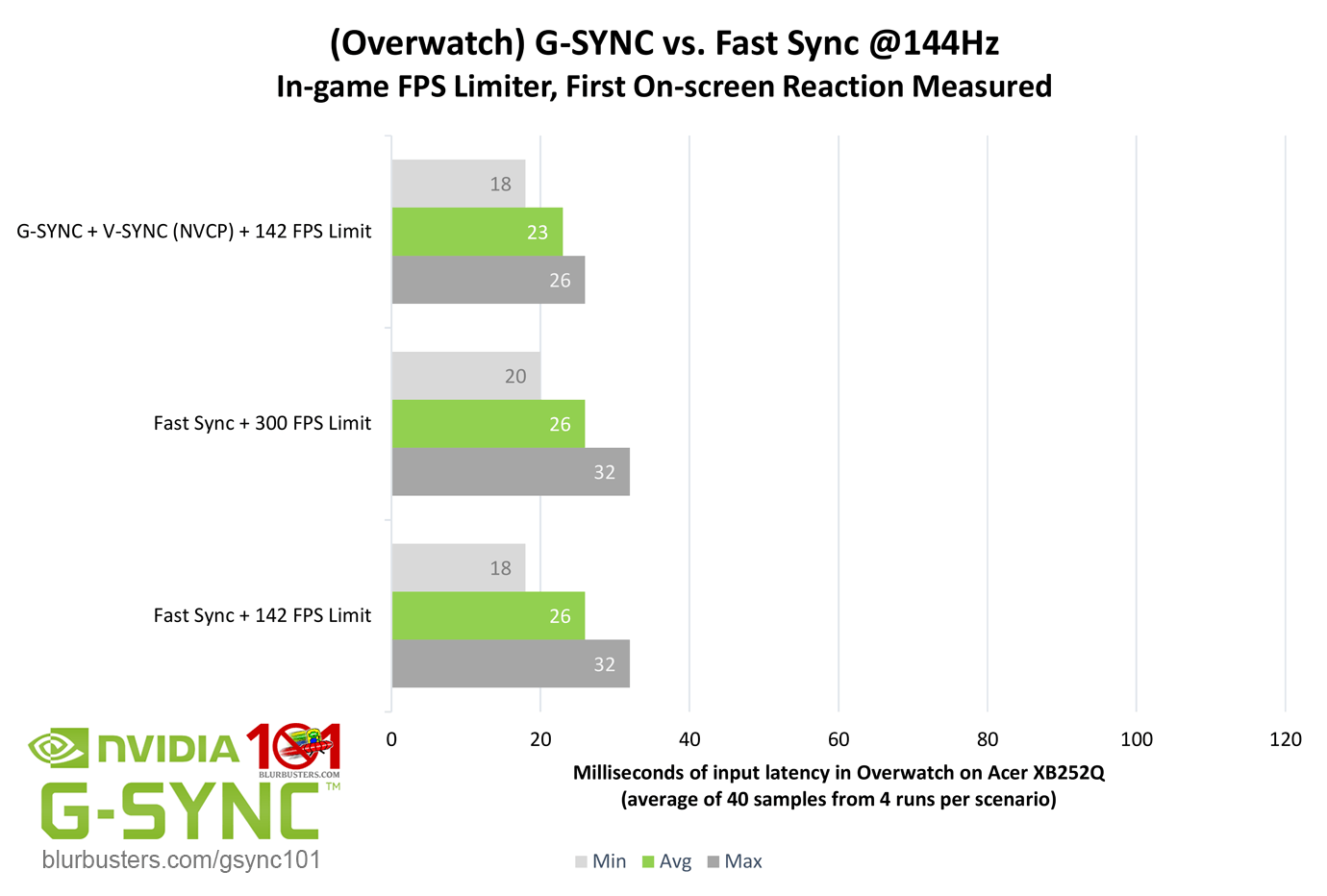

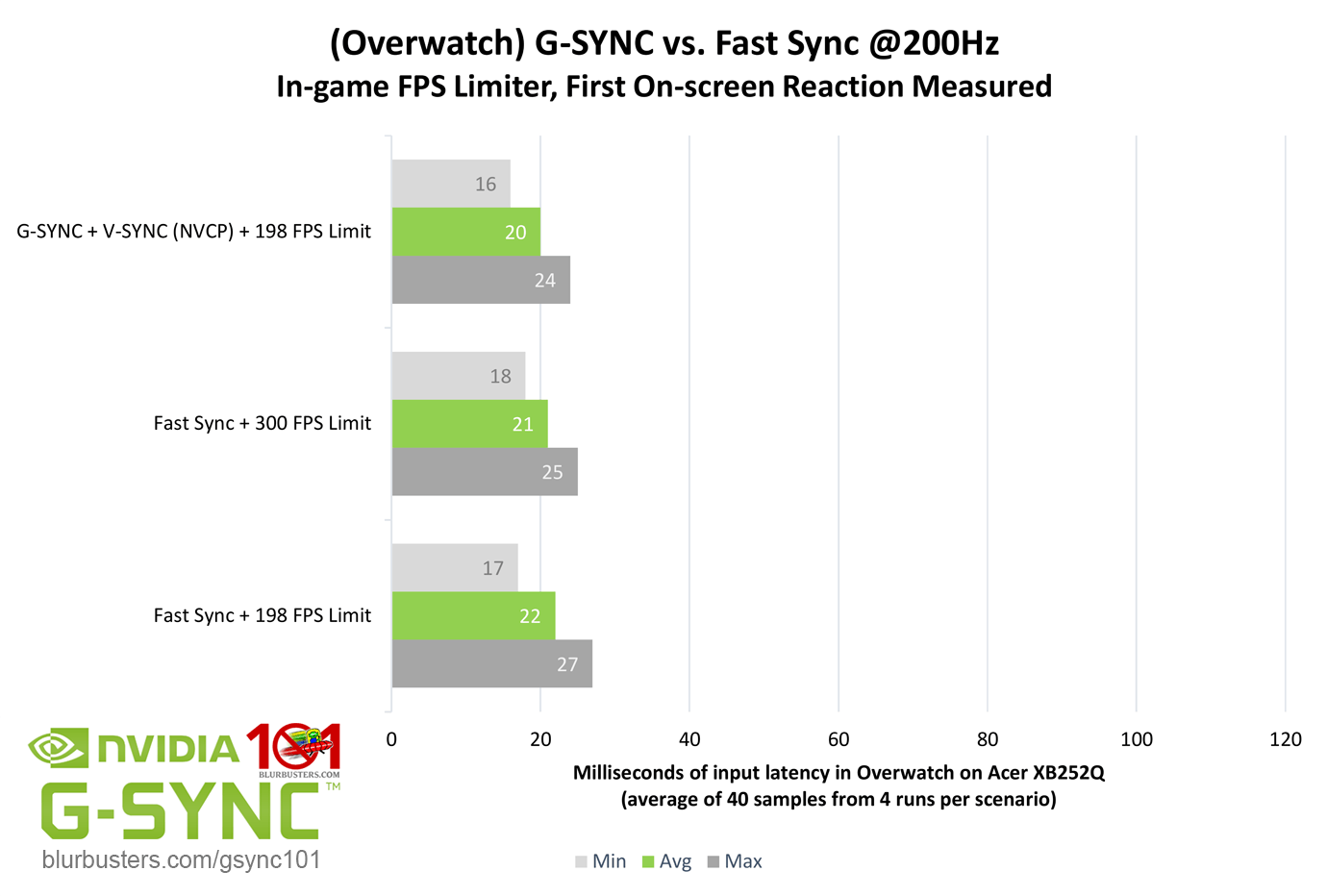

Evident by the results, Fast Sync only begins to reduce input lag over FPS-limited double buffer V-SYNC when the framerate far exceeds the display’s refresh rate. Like G-SYNC and V-SYNC, it is limited to completing a single frame scan per scanout to prevent tearing, and as the 60Hz scenarios show, 300 FPS Fast Sync at 60Hz (5x ratio) is as low latency as G-SYNC is with a 58 FPS limit at 60Hz.

However, the less excess frames are available for the third buffer to sample from, the more the latency levels of Fast Sync begin to resemble double buffer V-SYNC with an FPS Limit. And if the third buffer is completely starved, as evident in the Fast Sync + FPS limit scenarios, it effectively reverts to FPS-limited V-SYNC latency, with an additional 1/2 to 1 frame of delay.

Unlike double buffer V-SYNC, however, Fast Sync won’t lock the framerate to half the maximum refresh rate if it falls below it, but like double buffer V-SYNC, Fast Sync will periodically repeat frames if the FPS is limited below the refresh rate, causing stutter. As such, an FPS limit below the refresh rate should be avoided when possible, and Fast Sync is best used when the framerate can exceed the refresh rate by at least 2x, 3x, or ideally, 5x times.

So, what about pairing Fast Sync with G-SYNC? Even Nvidia suggests it can be done, but doesn’t go so far as to recommend it. But while it can be paired, it shouldn’t be…

Say the system can maintain an average framerate just above the maximum refresh rate, and instead of an FPS limit being applied to avoid V-SYNC-level input lag, Fast Sync is enabled on top of G-SYNC. In this scenario, G-SYNC is disabled 99% of the time, and Fast Sync, with very few excess frames to work with, not only has more input lag than G-SYNC would at a lower framerate, but it can also introduce uneven frame pacing (due to dropped frames), causing recurring microstutter. Further, even if the framerate could be sustained 5x above the refresh rate, Fast Sync would (at best) only match G-SYNC latency levels, and the uneven frame pacing (while reduced) would still occur.

That’s not to say there aren’t any benefits to Fast Sync over V-SYNC on a standard display (60Hz at 300 FPS, for instance), but pairing Fast Sync with uncapped G-SYNC is effectively a waste of a G-SYNC monitor, and an appropriate FPS limit should always be opted for instead.

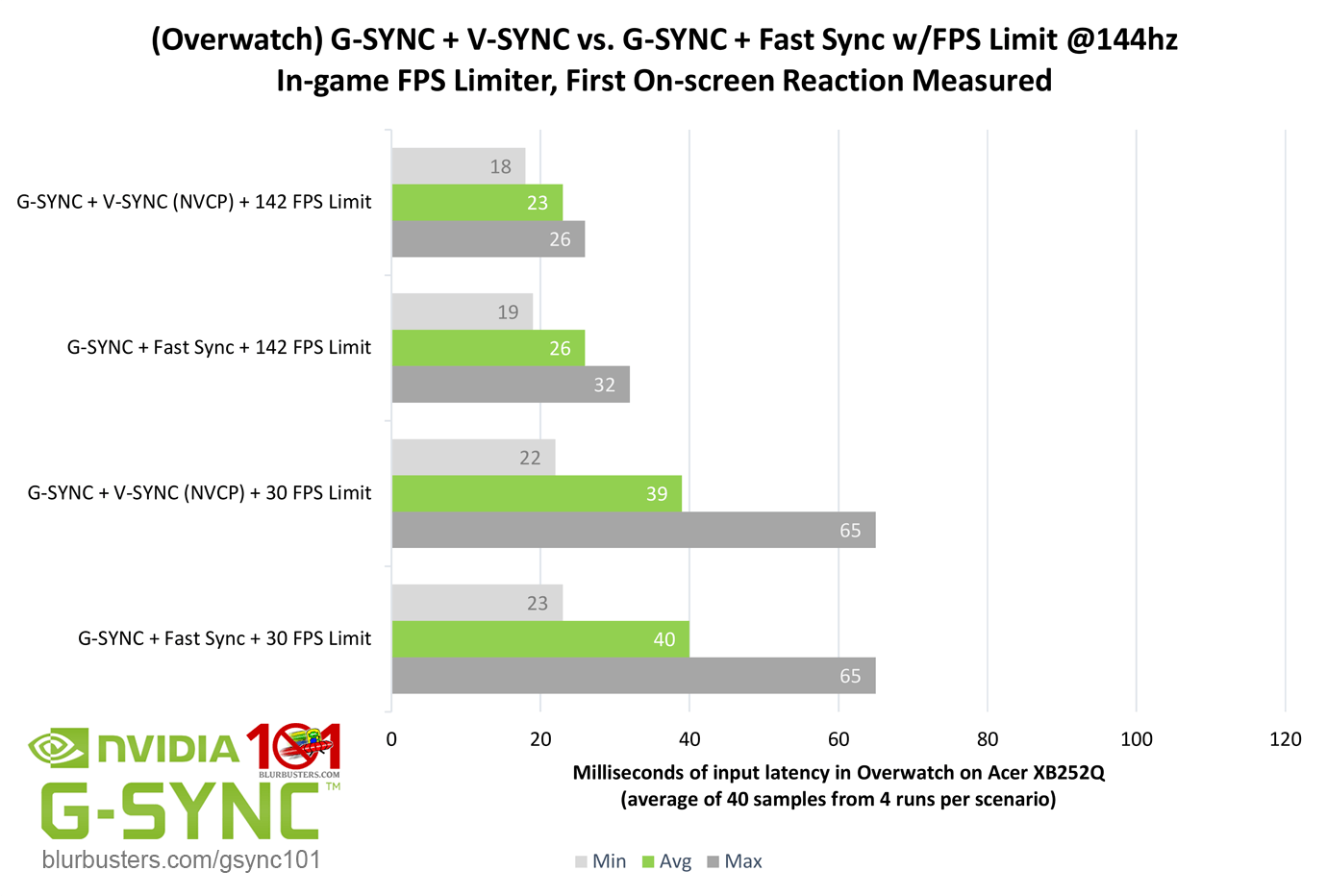

Which poses the next question: if uncapped G-SYNC shouldn’t be used with Fast Sync, is there any benefit to using G-SYNC + Fast Sync + FPS limit over G-SYNC + V-SYNC (NVCP) + FPS limit?

The answer is no. In fact, unlike G-SYNC + V-SYNC, Fast Sync remains active near the maximum refresh rate, even inside the G-SYNC range, reserving more frames for itself the higher the native refresh rate is. At 60Hz, it limits the framerate to 59, at 100Hz: 97 FPS, 120Hz: 116 FPS, 144Hz: 138 FPS, 200Hz: 189 FPS, and 240Hz: 224 FPS. This effectively means with G-SYNC + Fast Sync, Fast Sync remains active until it is limited at or below the aforementioned framerates, otherwise, it introduces up to a frame of delay, and causes recurring microstutter. And while G-SYNC + Fast Sync does appear to behave identically to G-SYNC + V-SYNC inside the Minimum Refresh Range (<36 FPS), it’s safe to say that, under regular usage, G-SYNC should not be paired with Fast Sync.